A Life Less Ordinary

I often read the obituaries in the Trusty Servant, not because I’m morbid but because they often offer fascinating insights into individuals’ experiences of pivotal events in the 20th century, some of which are starting to pass from living memory. Last November, I read an obituary that seemed even more extraordinary than most:

‘Cecil Herbert William (Bill) Hodges (Coll, 1935-40); died 14.11.2016 aged 95. Sen Cap Prae, VI, English Speech Prize and Kenneth Freeman Prize, Scholarship to Oriel College, Oxford 1 Class Mod 1942. He was commissioned into the Royal Artillery 1942 and landed in Normandy on D-Day and later served in Holland and Germany. He was one of the first British officers to enter Belsen and his letters home, full of the horror of that place, are now held in the Imperial War Museum. Demobbed as a Captain in 1945. He then started a successful career in the Treasury from 1947.

His most interesting job was as a Treasury Adviser to the UK Mission to the UN in New York 1961-63. He was loaned to Department of Economic Affairs 1966-68. He then went to the Cabinet Office 1972-74. He was appointed CBE for his work in the Treasury. On retirement he moved to the Cotswolds with his partner, Bernard Finn – their dinner parties were renowned throughout the area. Bill and Bernard took advantage of new legislation to form a Civil Partnership in 2003. Increasing infirmity persuaded them to return to London. Despite deafness and deteriorating eyesight he maintained his sense of humour and determined that the School should benefit from his will. Having been known as Cecil but always wanting to be Bill, he waited until the death of his mother aged 101 before he changed his name.’

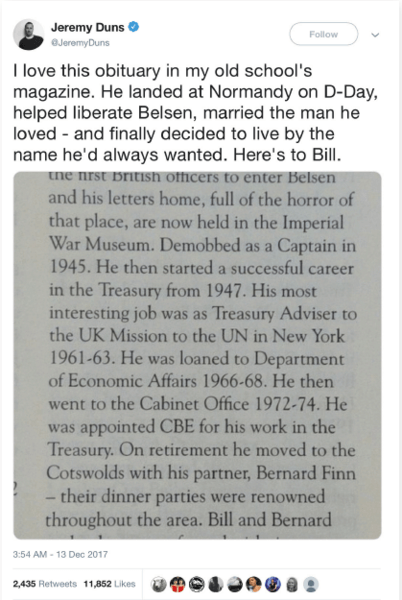

It’s easy to criticise social media – at best, people sharing mundanities and selfies, at worst causing geopolitical havoc – but sometimes it provides a welcome surprise. I’ve been on Twitter for nearly a decade and one of the most startling reactions I’ve received on the site was through a tweet about Winchester College.

I took a photo of these lines with my smartphone and tweeted the image along with this caption:

‘I love this obituary in my old school’s magazine. He landed at Normandy on D-Day, helped liberate Belsen, married the man he loved - and finally decided to live by the name he’d always wanted. Here’s to Bill.’

This had soon been shared by over 2,000 people and ‘liked’ by over 11,000. The Independent published an article on it having gone viral, while online magazine ‘LADBible’ ran a story headlined ‘Obituary For World War Two Veteran Shows How You Live Your Life To The Fullest’. A Spanish newspaper, El Confidencial, joined in, with an article titled ‘El obituario más increíble que te vas a encontrar este año’.

What was it about this particular obituary that sparked so much interest? I think it was partly the combination of the familiar and the surprising packed into such a short space. Here, in just 236 words, was the rich texture of a life that encompassed some of the most brutal events of the 20th century and ended in the free and tolerant society that had been won through overcoming them in the 21st. It was a love story, of course, but also a tale of personal integrity that presented a quiet, unshowy form of individuality. Bill Hodges lived a long and successful life his own way but, in what might have seemed a small matter to some, he delayed his own wishes so as not to offend his mother.

At Winchester, Bill – let’s call him that – was a scholar who won several prizes: the Ross Homer Prize for Greek and the junior Kenneth Freeman Prize for classical literature/art/archaeology in 1938; an exhibition in 1940; the silver medal for English Speech and the senior Kenneth Freeman Prize in 1940. He was runner-up in a few others. Thanks to back issues of the Trusty Servant and other sources, we know he was quite the all-rounder. He played Win Co Fo for College in November 1939, and a month later played the bassoon at the school concert. He was briefly a member of the Debating Society, and was vice president of SROGUS, the Shakespeare Reading and Orpheus Glee United Society.

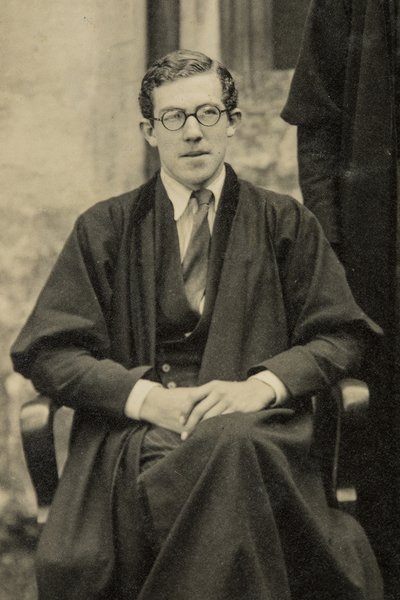

For younger OWs this all sounds within the realm of normality, even if some of the prizes no longer exist. But looking at the photograph of him seated with his classmates in Cloister in 1940 is sobering when one considers that four years later this rather severe, pale-looking young man would be on the beaches of Normandy.

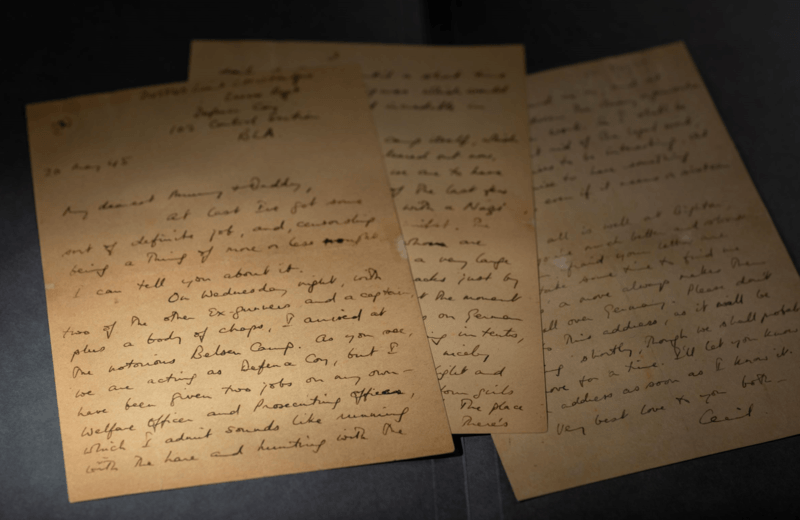

His two letters home held at the Imperial War Museum offer a snapshot into his mentality during and directly after the war. In parts he gives off an almost breezy tone, presenting a stiff upper lip. In a letter to his parents in September 1944, he filled them in on ‘what I’ve been up to since D-Day’, most notably his involvement in the Battle for Caen and its aftermath:

‘We then spent several weeks in holes in the ground being pestered by Boches and mosquitoes, but more by the latter … When the Boches started to break and fall back, we had a pretty hectic fortnight chasing them along a line not far in from the coast as far as the Seine. We kept the guns pretty well on the heels of the ‘para boys’ and I believe some of them christened us Bob Hope’s Commandos – the C.O.’s real Christian name, though, is Maurice.’

He described the ‘crowded little seaside strip’ as ‘very dusty’ and ‘rather smelly’; after hammering away at the positions, there was nothing but ‘broken walls, and torn up fields stinking with dead cattle and, after the attack, dead Germans.’ The other surviving letter is from ‘the notorious Belsen camp’ on 20 May 1945, just 13 days after victory had been declared in Europe. Bill tells his parents he has been given two jobs, that of Welfare Officer and Prosecuting Officer:

‘You’ve probably read about Belsen; it wasn’t so much a torture camp as a dump where the Germans sent the human beings they didn’t want, and let them die of starvation and disease. The medical staff, helped by the Red Cross and about a hundred medical students from London hospitals have worked wonders in the month or so since the camp was liberated, though the daily death rate until a short time ago was still in figures which would probably have seemed incredible in pre-war Europe.

The concentration camp itself, which we call Camp I, is cleared out now, and tomorrow evening we are to have a ceremonial burning of the last few huts, which will perish with a Nazi flag at half-mast in the midst.’

Around half the camp’s inmates were still sick, he reported, while electricity and dignity was slowly being restored. The letter is matter-of-fact: there are no wry jokes as in the earlier letter, but neither is this a cry of anguish on entering a place most would consider hell on earth. It was probably natural to skirt over such sentiments when writing to his parents, who would have been distressed if he had seemed overly shaken, and perhaps he also realised that forging a sense of normality again wouldn’t be helped by dwelling on the nightmares that had just been experienced.

For me, the straightforwardness of the letter is its most haunting aspect. Bill saw the effects of the Nazi regime first-hand, but even then he had not experienced them himself. The human mind is capable of remarkable feats of adapting. His language is vivid and condemnatory but by now the camp was already ‘notorious’ in the eyes of the world. The atrocities at Belsen seem to have been within the realms of what he had expected – or at least had been rapidly ordered to be such in his mind. Perhaps Hannah Arendt’s famous phrase ‘the banality of evil’ can apply to the witnessing of it as much as to its execution. After six long years of war, many Britons were shocked by the extent of the Nazis’ cruelty when they saw news footage of the camps, but they knew such things had happened, and that the Nazis were evil. Indeed, six years of being told that they were fighting the greatest evil to face the world probably meant that the effect was dulled for some: it was a matter of faith, and might have been more shocking to Bill if he had entered a camp that had treated its inmates with a shred of human dignity instead of deliberately leaving them to die.

Behind the simple lines is a harrowing darkness. Did he think of it much in his later years, perhaps quietly in a corner at one of those dinner parties in the Cotswolds as Bernard opened a bottle of wine for guests? Or did he manage to put the war aside, cast adrift from the rest of his life?

For me, the true power of Bill’s story is its unknowability. In reading about his eventful, fascinating life, I long to know more – to have known him, and what he felt and thought. But an obituary is merely an outline of someone’s life, and one that comes too late to be acted on in that way. I often come across people who I wish I had sought out to interview or simply talk to while they were still alive – no more than here. In the absence of knowing more, though, and in the spirit of what he left behind, all I can do is be thankful others were also interested in his life, and offer a toast to him once more: so here’s to Bill.

C H W Hodges (1935-40; Cap. Prae)

Jeremy Duns' tweet about Bill Hodges went viral

Head back to stories

Head back to stories