Painting by Numbers - how the pandemic will affect the economy

In this article, Ben Gould, Economics don, explores how the pandemic might impact economic recovery.

I love statistics.

After having lost half of the readers in three words, let me explain why. Statistics can help us to get closer to the truth about a situation. They can tell us important things, but each indicator misses out crucial information. No one statistic can ever tell you the full truth. Painting with multiple colours and different strokes will always create a more detailed and representative picture. I have highlighted and attempted to contextualise some important statistics that help our understanding of COVID-19’s impact on the UK Economy. It is no secret that the economic consequences of the lockdown have been immense. This inevitable, in order to protect the health of the nation. This economic disruption is likely to be largely temporary, although the longer the lockdown continues and the slower the path to a cure, the more permanent and damaging its effects. By looking at some historical scenarios, we can hypothesise the rebound and likely prospects of the UK (and, to an extent, world) economy. The full scale of the picture will become much clearer in time and I suspect it won’t make for fantastically positive reading.

Wellbeing and Confidence

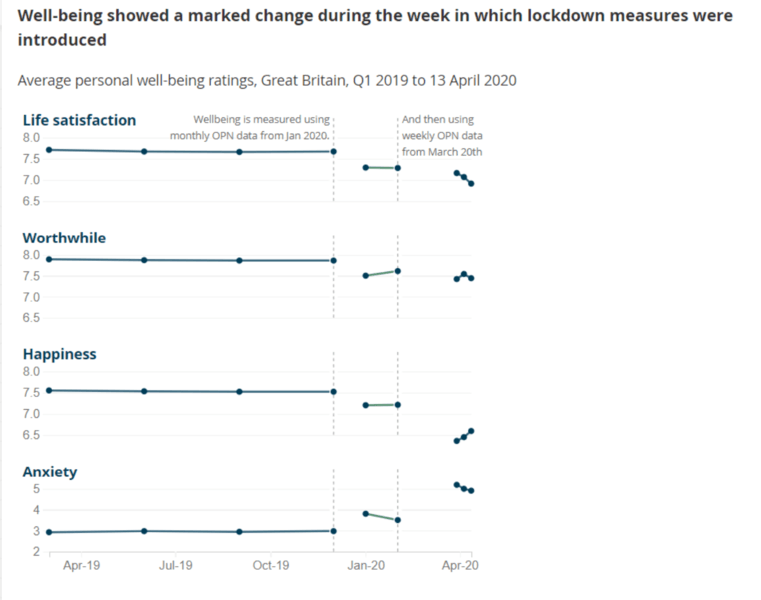

Economics is normally associated with financial figures, stocks and GDP. In fact, at its core, it is about people and the way they interact with each other and the world. Its primary focus should be on the welfare of people and the Earth. Many countries regularly measure people’s wellbeing, through indicators such as Anxiety, Happiness and Life Satisfaction.

Source: Office for National Statistics

Unsurprisingly, people are seemingly significantly less happy and satisfied and more anxious. The biggest single factor is the restriction on activity, rather than financial concerns. Financial concerns are likely to become more of an issue the longer shutdown lasts and the quicker government support is withdrawn.

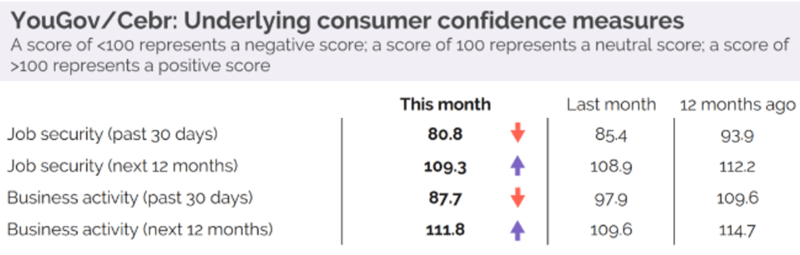

Some good news, people feel confident that the economy will bounce back fairly quickly. This confidence is seemingly well placed, as a vast majority of businesses will be able to resume operation quickly after they are authorised to do so.

High confidence can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. If people believe the economy is going to be good in the future, they feel more happy to spend money now, leading to businesses having more money, expanding and hiring more people, giving more people more money and improving the economy in the future.

Much of this confidence is due to the government’s short-to-medium term measures put in place to protect:

Employment

23% of the workforce furloughed (Govt stats)

2.3m Universal credit claims (DWP)

57% of businesses have falling revenues (British Chambers of Commerce)

Changing employment practices are perhaps the most visible of the pandemic’s economic effects - very few of us are working in the same way that we were. You will likely know someone who has been laid-off or furloughed. Money is very tight for a lot of people – food bank usage is at record levels; many businesses are struggling, and a significant number have ‘fallen through the cracks’ of the rescue efforts.

There has been, however, an unprecedented governmental response. The furlough scheme has meant many are currently not working but are still receiving at least 80% of their salaries. This scheme will help to remove many immediate financial worries. It does, however, put a huge strain on:

Government spending

£225bn (Government borrowing, Apr-Jul, DMO)

Through a combination of tax breaks, furlough schemes, business support and other expenditure, the government is going to spend more money this year than any UK government has ever done. And it’s not even close.

Before this year, the largest public deficit (the difference between government expenditure and tax revenue) was £147bn (in 2010). The cost to the government in just four months will comfortably exceed this (N.B. not adjusted for inflation. This eye-watering amount is manageable, although how long that will remain the case is debateable.

The economic damage of not undertaking this level of expenditure is likely to be far more dangerous than allowing market forces to take hold and people to suffer.

These government schemes are protecting much of the population, but certain groups are more at risk. The increased risk to older people has been well publicised, but the health implications have also shown to be worse for black Britons – largely due to structural inequities meaning BAME people are more likely to be working lower-paid, higher-risk jobs.

Historical recessions reveal disproportionate impacts on ethnic minorities and the poor to be the hardest hit. For example, in the Great Depression, black Americans were more severely affected, with half unemployed and more than 45% of black wealth lost. This pattern is still found in more modern recessions – albeit less pronounced.

We must ensure that the most vulnerable are protected from the devastating economic and health impacts that the pandemic can cause – so as not to repeat the mistakes of history.

It’s hard to sugar-coat: these statistics paint a pretty bleak picture. The outlook for the future is mixed. A lot depends on the length of time between the easing of lockdown and a vaccine, as this will impact how much confidence both people and businesses have. With the right support, people are resilient, and many businesses are ready to spring-back.

Predictions for economic recoveries are always very difficult and economists get a lot of stick for ‘incorrect’ forecasts (often fairly!). The Bank of England are predicting a sharp rebound to previous levels, before continuing with more growth. This seems slightly optimistic to me (read: virtually impossible, with no historical precedent).

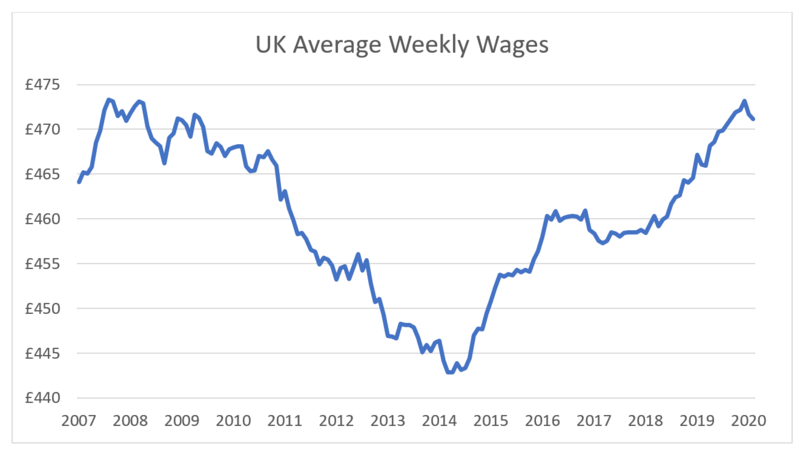

In my lifetime, only the global financial crisis (GFC) can come close to matching the economic shock of coronavirus. For many, economic reality has never been the same post-GFC – showcased by real wages (adjusted for inflation) still hovering at 2008 levels.

This recovery has been brutal, affecting lower-income people and regions more severely than more affluent areas. We cannot afford another similar recovery, especially as those already suffering are likely to be the first and hardest hit.

The good news is the circumstances of this recession (assuming it will become a recession) are very different to the GFC. The GFC was caused by faults in the banking system, which meant the financial mechanisms had to be rewritten, stiffening the wheels of by which people can benefit from extra confidence and growth. This time around, we have an external shock which shouldn’t affect our key institutions permanently.

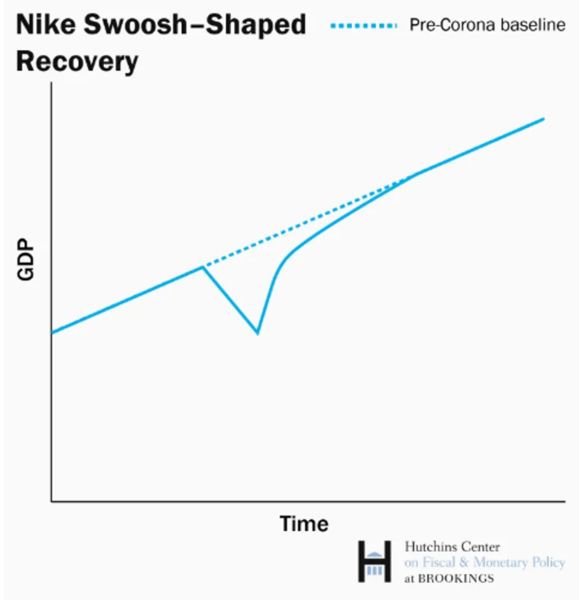

If the circumstances are different, what is this recovery going to look like? Let’s have a look at reasonable best- and worst-case scenarios.

The lockdown is likely to be released in stages, in order that we don’t overwhelm the health services with too many new cases at the same time. Full ‘normality’ is likely some way off, and, as such, we are unlikely to see a swift return to pre-pandemic levels of economic growth.

The Nike-swoosh recovery sees a primary ‘bounce back’ caused by extra spending from pent-up demand from the lockdown period – as people make the most of their new freedom. This is then followed by a steadier return to steady growth, with an opportunity for redirecting economic systems to greener and more equitable ways of working.

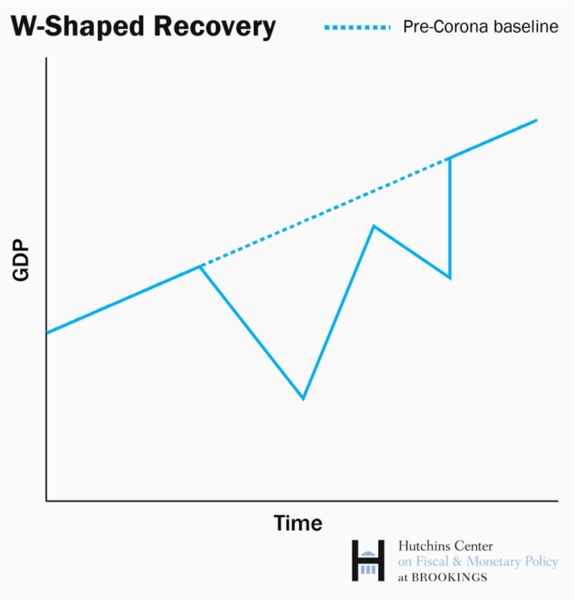

Releasing lockdown measures too soon and too quickly will result in a new influxes and cases, along with a return of more stringent measures. This could cause a ‘double-dip’ recession, which is likely to result in more long-term and permanent issues.

This situation is the worst of both worlds. There is no trade-off between health and the economy – they are inextricably intertwined. Mr Johnson has spoken at length about the dangers of this scenario, hopefully, this threat will be taken seriously.

It is too early to know exactly what the economic consequences of the pandemic are, and even earlier to know what they will be. For now, we must keep reducing the risk of transmission as much as possible, whilst encouraging others and businesses to do the same and support the most vulnerable to the fullest extent possible – the price of a life is too high (although it’s only £1.8million according to Department for Transport). The College has made drastic changes in recent months. I hope our recovery to normality will be as swift and seamless as possible.

References

https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/05/04/the-abcs-of-the-post-covid-economic-recovery/

https://phys.org/news/2019-10-fatal-flaws-uk-price-life.html

Head back to stories

Head back to stories